The Shape of Speaking

The coffee we drink, the clothes we wear, and the people we see are all a complex function of cultural influence.

There is an argument to be made that globalization is taking us to that point, for better or worse the world is becoming more uniform. Whereas 25 years ago American fast food was strictly an American phenomena, now KFC or Burger King can be found in mall food courts around the world.

The forces of globalization have even influenced how we speak, slang is becoming less region specific and instead has a universality to it. And perhaps most consequently the variety of languages we speak has diminished greatly [1].

Most languages have seen a marked fall in favor of two:

Both English and Chinese have taken command of the world both easily breaking the 1 billion speaker barrier. We have basic intuitions for how and why languages fall and rise. They are heavily tied to population and the dominant world power at any given time, but independent of that have we gotten it right?

In my opinion getting it right means that the primary languages of the world should be diverse filled with a rich assortment of grammars, styles, sounds, and the works.

One potential solution to quantifying linguistic diversity is through the development of a Language Similarity Index (LSI). Using a LSI we could help quantify how diverse the languages we seak are

Why Are Linguists Afraid of Numbers?

Till this point I’m still sniffing around for some concrete numbers. I want a single metric to show me how agglutinative Russian is. Is English 33% more fusional than Danish?

But this search for rigorous metrics is likely fruitless. Linguists are hesitant to assign numerical values to language features because language is complex and too fluid to be contained by a set of static figures. What's more, any attempt to quantify language runs the risk of oversimplification and inaccuracy.

But I don’t necessarily buy that wishy-washy answer. In the 1950s we thought that sports were just about who wants it more, but now we have an entire field of sports analytics. Perhaps a Language Similarity Index can be developed if we think creatively and find ways to measure language that go beyond the traditional methods.

Approach 0: The Learning Model

One of my first thoughts about how to quantify this LSI was time taken to learn a language. By removing other extraneous variables and just mapping starting with language A how long does it take to learn language B.

The biggest burden to this approach is that there is no way to remove extraneous variables. I can’t just lock a group of Russian speaking children in a room, give them Duolingo, and start a stopwatch. But even if we were able to pull this off it raises other questions like “what does it mean to know a language?”.

There isn’t much quantitative data on second language acquisition however, the Department of State provides guestimations about how long it takes to learn a second language as a native English speaker [12]:

![[12]](/assets/img/weeks-to-learn.png)

This science is very inexact and similar metrics don’t always exist for other languages. Given that rigorous longitudinal tests on second language acquisition don’t exist yet, it’s safe to say there’s a reason why.

Approach 1: Wait I Know That Word!

This approach is going to be very simple. Starting with the words in the dictionary of any given language, we can compare that dictionary to another language’s and see how many words are similar.

This is called lexical similarity. There are lots of ways to compute the similarity including Jaccard Similarity [13]:

$$ J(L_1, L_2) = \frac{L_1 \cap L_2}{L_2 \cup L_1} $$

Which basically computes how many words in two language’s dictionary are the same over all the words in both dictionaries.

Now I could do this for all pairwise combinations of languages, extracting words from dictionaries, defining similarity, etc. but there are lot’s of resources online that already do this.

Using the lexical similarity between a set of arbitrary languages we are able to build this table (where higher numbers mean more similar) [14]:

![[14]](/assets/img/Screen_Shot_2023-03-24_at_3.26.37_PM.png)

This is getting to the essence of what I’m looking for, but it’s missing something. The words that comprise a language don’t define a language. The way people speak, sentence construction, etc. are all components of language. So let’s dig deeper and go beyond the lexicon.

Approach 2: The Language Tree (Fancy)

We have previously talked about how the history of language creation has left remnants of a tree like structure, but how about constructing that language tree artificially trying to build a more functional language tree.

We can attempt to do this by building a decision tree that recognizes written language patterns and uses them to classify languages based on their features. Hopefully the resulting language tree can shed some light onto the relationships between languages.

There are a couple of complications with this approach. First, it is quite impractical to classify 6000+ languages because the decision tree that we get will probably overfit and have no interoperability. Second, this approach relies on having accessible training data and for a language like Yessan-Mayo spoken in Papa New Guinea by around 8,000 people [15], I’m not confident that they have translated the literary works of Shakespeare to create a training corpus.

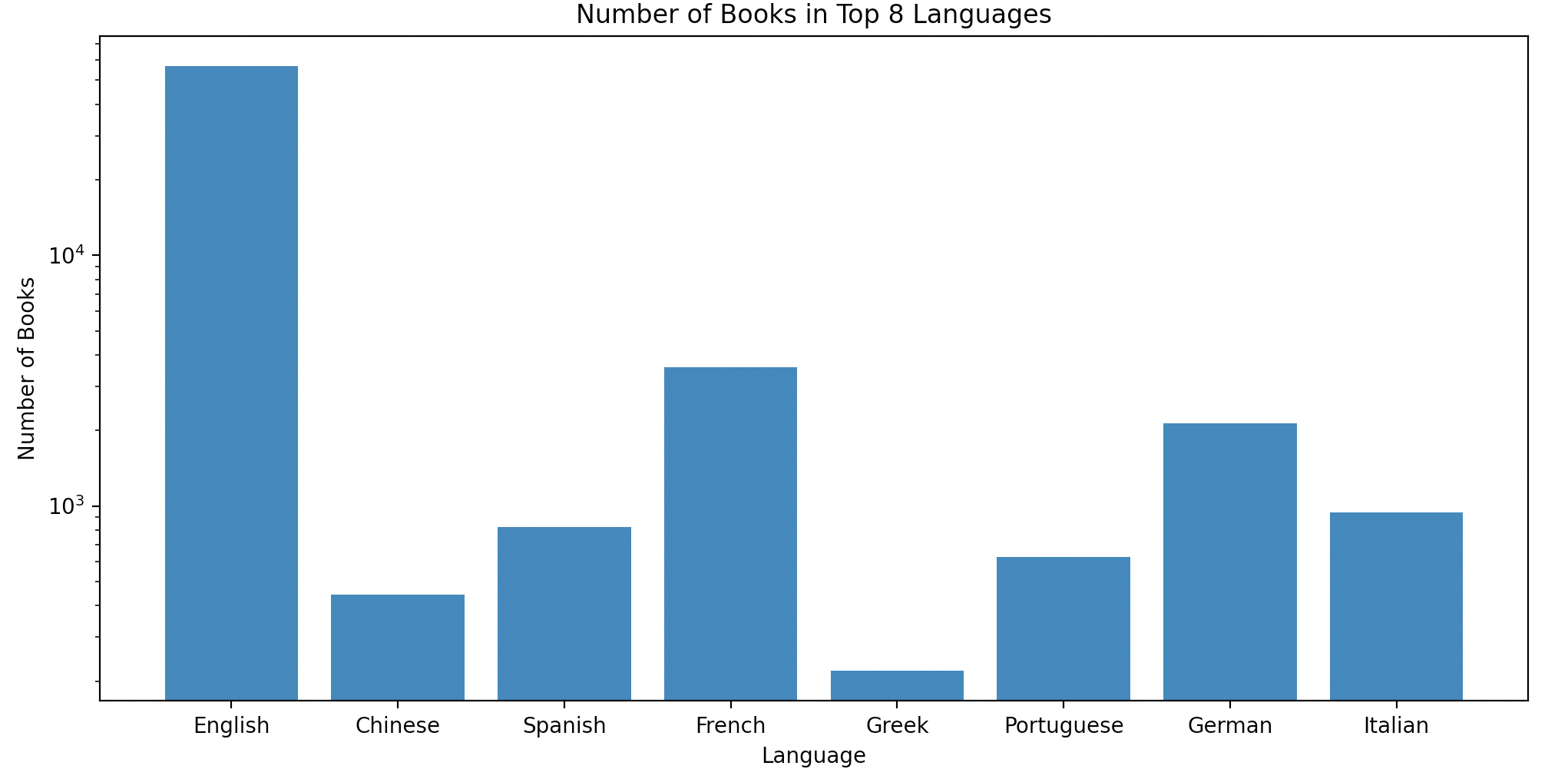

The training data was collected using Project Gutenburg which has archived countless ebooks and provided translation services for many of their works [16]. This training set also informed the languages we wish to classify.

Although, Project Gutenberg’s translation services are good there is still a heavy preference towards European literature. This forces us to narrow our scope towards the languages that have enough written corpi. Even though Chinese and Greek exist on the Gutenburg Project often their text gets garbled during the translational process so we have to narrow our scope even thinner to languages with latin alphabets.

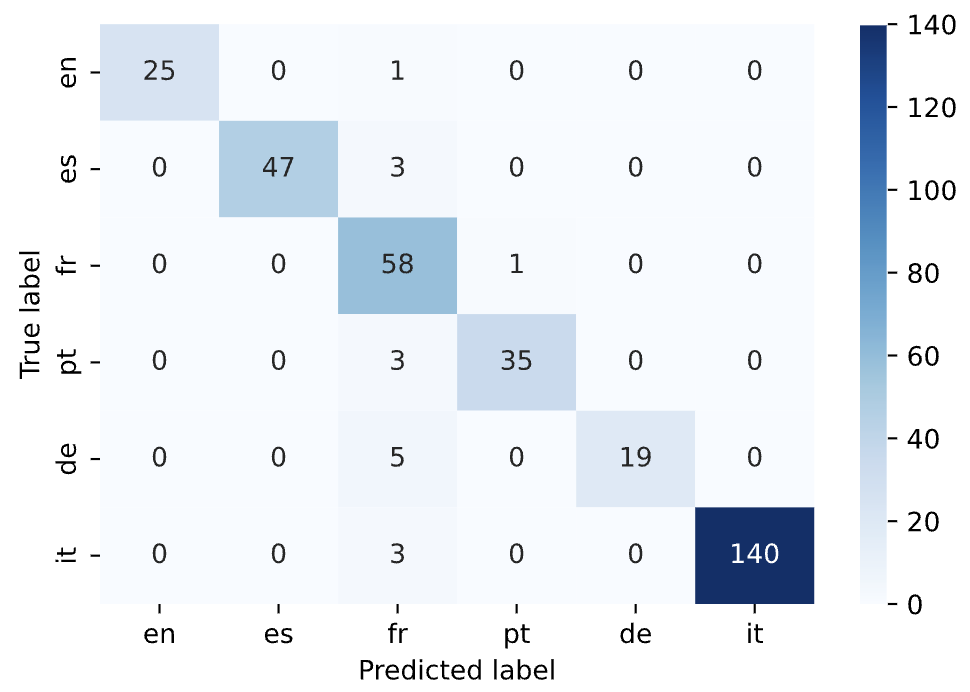

After, this decision tree was created we generated the following results:

- Accuracy (95.29%): The most intuitive evaluation metrics, in our testing how many predictions did we get right.

- Confusion Matrix: We can make sense of the confusion matrix qualitatively by making inferences like French is the most common false positive.

Now that we have sort of guaranteed that this model isn’t a pile of garbage let’s print the architecture in order to generate our functional language tree.

Well there isn’t really much to say, there is no aesthetic to this tree so don’t even try to zoom in and risk straining your eyes. I imagined Portuguese and Spanish would occupy similar branches, German and English would be interconnected in some sort of way, and generally language features to shine through in the decision making model of our tree but that is far from the case.

Machine Learning is a peculiar thing, accuracy and precision seldom guarantee that a model is human understandable. Although there are some ways we can quantify Language Similarity through a confusion matrix of a decision tree I feel as if this approach is straying too far from the spirit of a Language Similarity Index, on to the next!

Approach 3: Back and Forth and Back and Forth

At this point I was left scratching my head thinking about what to do to quantify a language similarity index. The inspiration for this next approach comes from a style of internet humor that existed 5-10 years ago. Back then most translation services were bad, bad enough that you could put a prompt through translate it to a different language a couple of times and you would be left with an absurd rendition of your original text.

In 2016 Google Translate moved from a statistical machine translation approach to a fancy-schmancy neural translation design and has gotten better [17]. But it’s still not perfect, and in that imperfection we may be able to find our LSI.

My proposed approach involves feeding a set of prompts in for example English, translating those to German, and then back to English then measuring how well the prompt was preserved. My assumption is that if more prompts are preserved for a particular pair of languages those languages are more similar and vice versa.

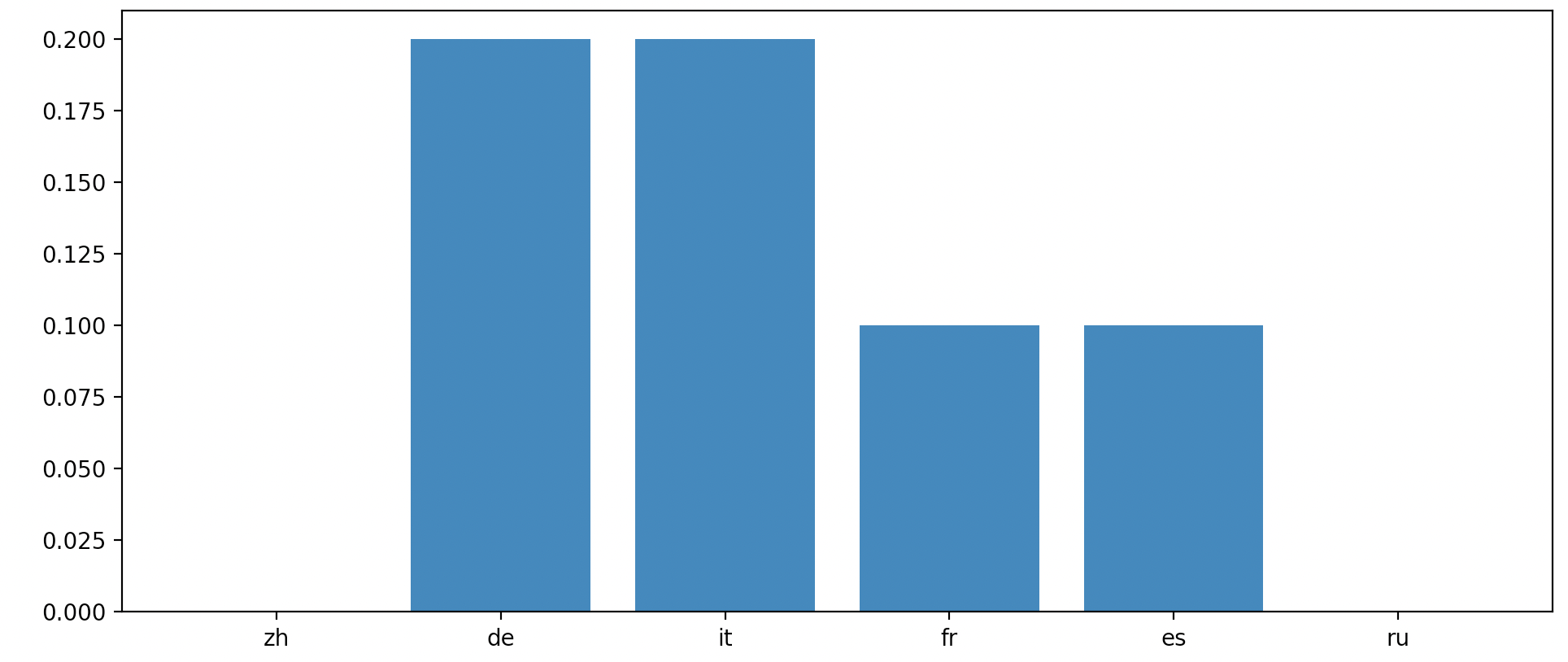

The translation accuracy of English to Chinese, German, Italian, French, Spanish, and Russian and back was captured here.

Here accuracy was defined as complete similarity from the original to the double-translated. This sample was only run over ten unique sentences for each language, but the original results are promising. Let’s see what happens when we introduce more languages, more tests, and better datasets [18].

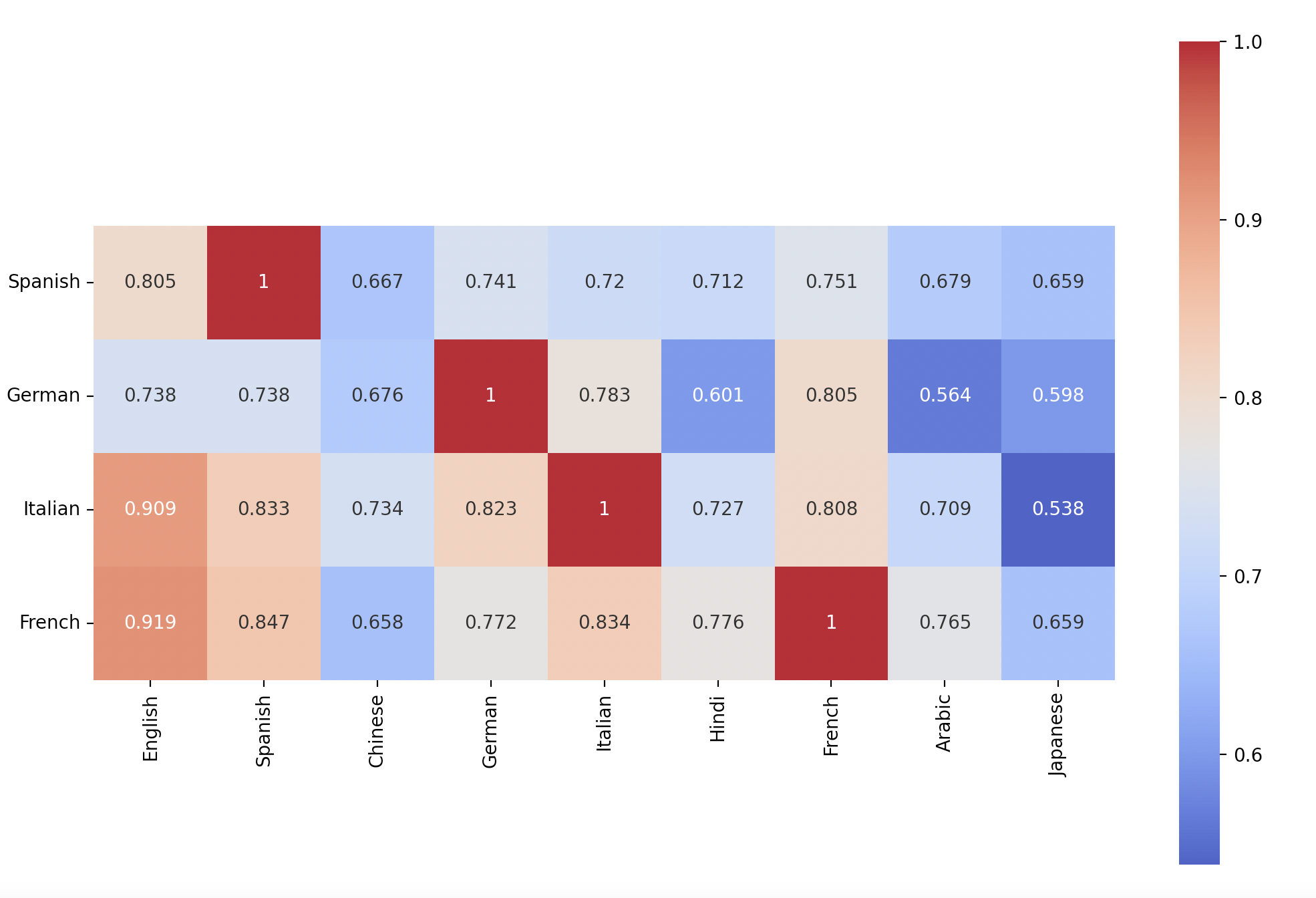

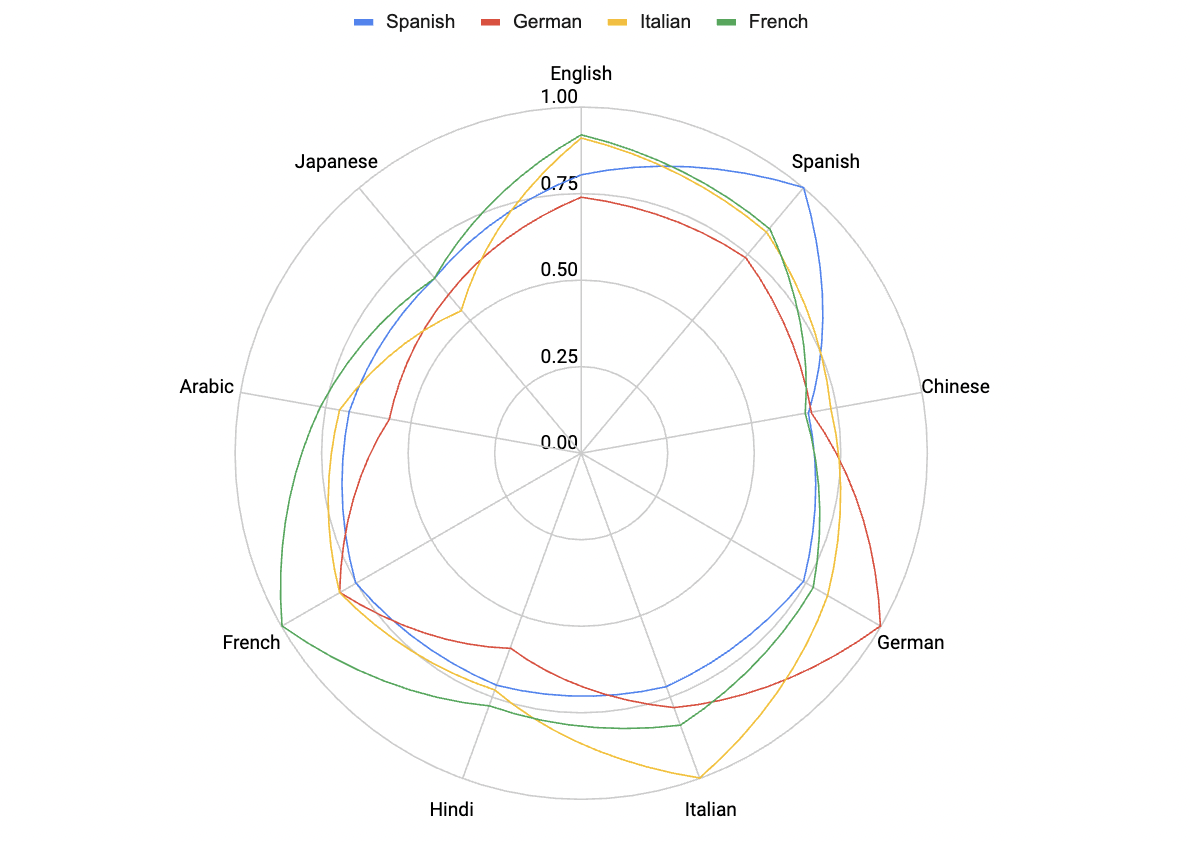

For this new and improved approach we measured the translational accuracy of the Romance languages between themselves and to Chinese, Arabic, English, and Japanese. Also, instead of measuring translational accuracy as a binary hit or miss we use the normalized Levenshtein Distance between the original and the back-translated string [19].

The most important thing to take into consideration is that not all language translation is supported equally. There is a preference towards Latin Alphabets and English specifically. Regardless this translation model seems to support our understanding of language. Romance languages are closely correlated with each other. Arabic, Chinese, Japanese, and Hindi remain fundamentally distinct from these languages.

Now I was going to run more tests among more language and normalize for translator accuracy, but unfortunately I ran out of API credits and I’m not interested in spending money on this paper. So we are going to leave it at that.

Wrap Up

What have we learned from the development process of an LSI? First and foremost, perhaps I have underestimated linguistics and NLP. It is hard to quantify anything linguistic. Wherever there is a rule there is an edge case. Similarity as a construct works well for comparing objective data like height or weight, but language is a fluid object. Asking, which two languages are most similar is akin to asking “How similar are two pieces of artwork?” Yes there are historical artifacts and general stylistic principles that can guide similarity but language is innately subjective and unique.

References

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19

![[1]](/assets/img/visualization_1.svg)

![[1]](/assets/img/visualization_(2).svg)