Blindfold Chess and Beautiful Monkeys

Playing chess is hard, but I would wager that playing chess blindfolded is harder. On top of the usual strategy and forethought that goes into regular chess you have to remember the board’s position at all times.

What would happen if a normal person wanted to play chess blindfolded? It probably wouldn’t bode well. To make things fair I could pair them up against another normal person equally blindfolded and clueless … that’s where the real fun begins.

Any Monkey Can Beat The Market

Most people have heard this quote about the stock market [1]:

“A blindfolded monkey throwing darts at a newspaper's financial pages could select a portfolio that would do just as well as one carefully selected by experts.”

Aside from the glaring disrespect thrown towards monkeys and their financial acumen, the quote poses an interesting question. When is randomness better than non-randomness. We have all encountered a similar scenario on a multiple choice test where maybe a random one-in-four option is better than overthinking it.

Does this same principle apply to chess? Most of us would probably say no. Chess is a game about precision, tactics, and forethought that dart throwing apes could never pinpoint.

But the guarantee of complete randomness coupled with the forgivingness of infinity can produce weird results. The infinite monkey theorem [2] (an unusual amount of monkey related references) states that:

“Given an infinite amount of time, a monkey randomly typing on a keyboard would eventually produce a complete Shakespearean play.”

In the same way, even with the added challenge of playing completely blindfolded, the randomness of the moves combined with enough trials can guarantee that a beautiful game of chess will emerge.

Let The Games Begin

Implementing a random chess bot is a much easier problem than creating a chess solver, and the execution of this was pretty straightforward:

def play_random_game():

board = chess.Board()

while (not board.is_game_over()):

moves = list(board.legal_moves)

random.shuffle(moves)

board.push(moves[0])

analyze_board(board)

for i in range(1000):

play_random_game()

Basically each turn there was a list of legal moves, we picked a random legal move, and kept moving until the chess game reached a terminal stage.

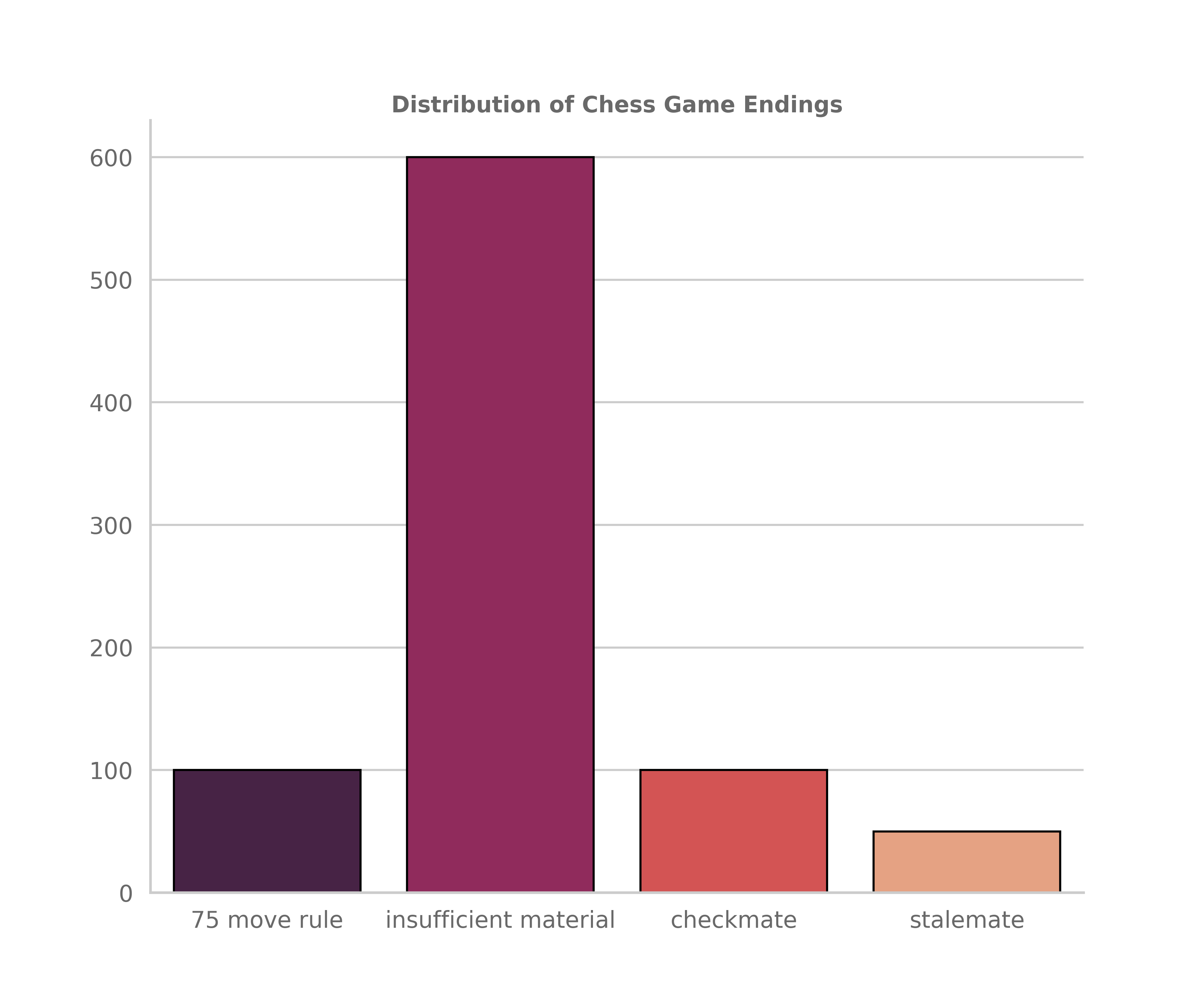

The terminal stages were qualified as a checkmate, stalemate, and insufficient material which are all pretty obvious. I also included the 75 move rule and 5 move repetition as my other terminal stages.

1000 games of chess were played and I didn’t have time to analyze each game individually, but within that set are games we would probably recognize as normal chess and also ones that mutilate the very essence of the game. So here are the results:

The least surprising result from this whole analysis was how many games terminated by insufficient material. This is natural in the absence of strategy or forethought, when random moves result in sub-optimal captures the board eventually dwindles down to an insufficient material state.

On the other side however, it was surprising that around 20% of games resulted in checkmate - outpacing both the 75 move rule and stalemate results.

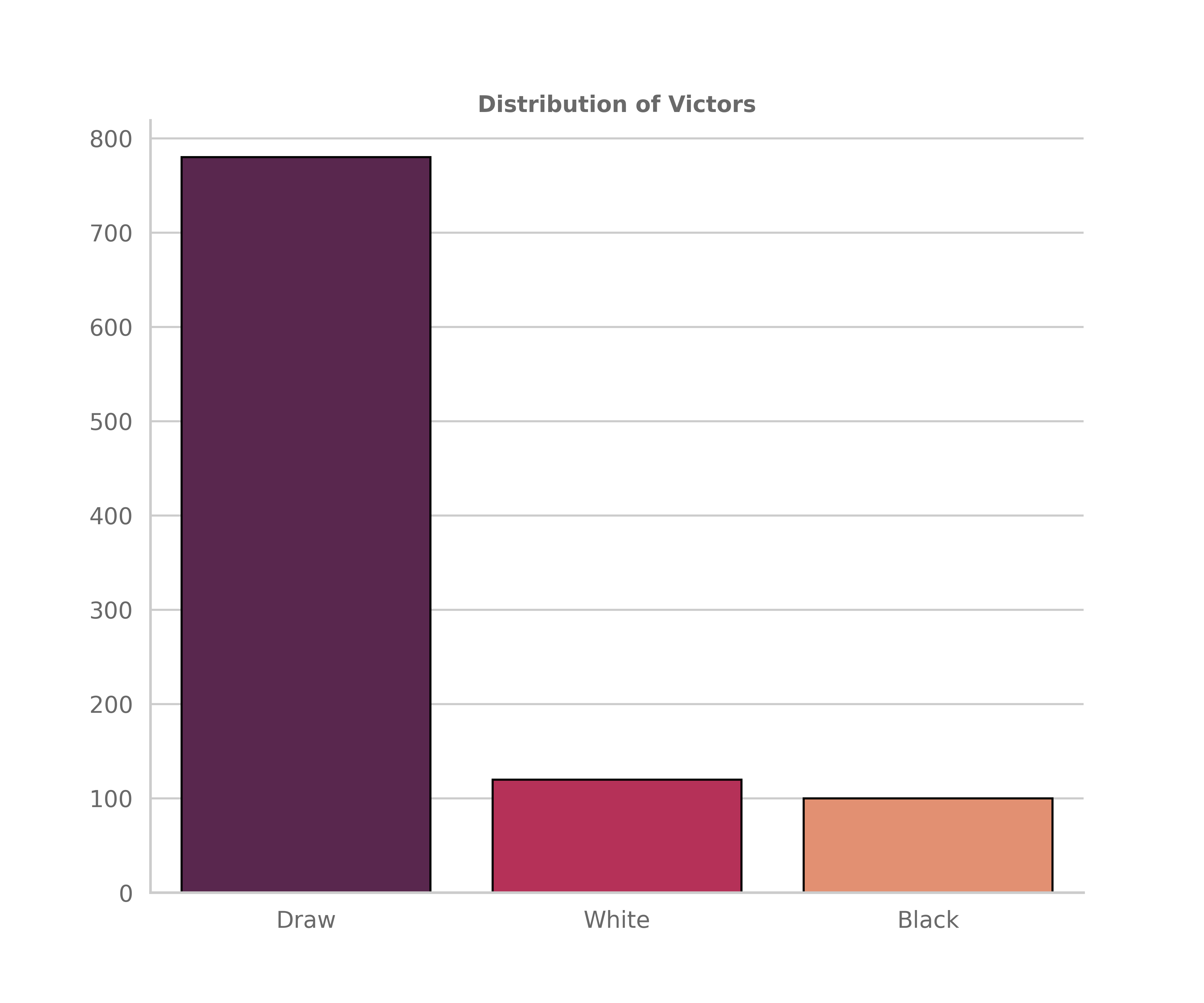

As a corollary of the first datapoint a mind-numbing amount of these games resulted in draws. Within the games that didn’t result in draws there looked to be a slight but noticeable advantage possessed by the white pieces winning.

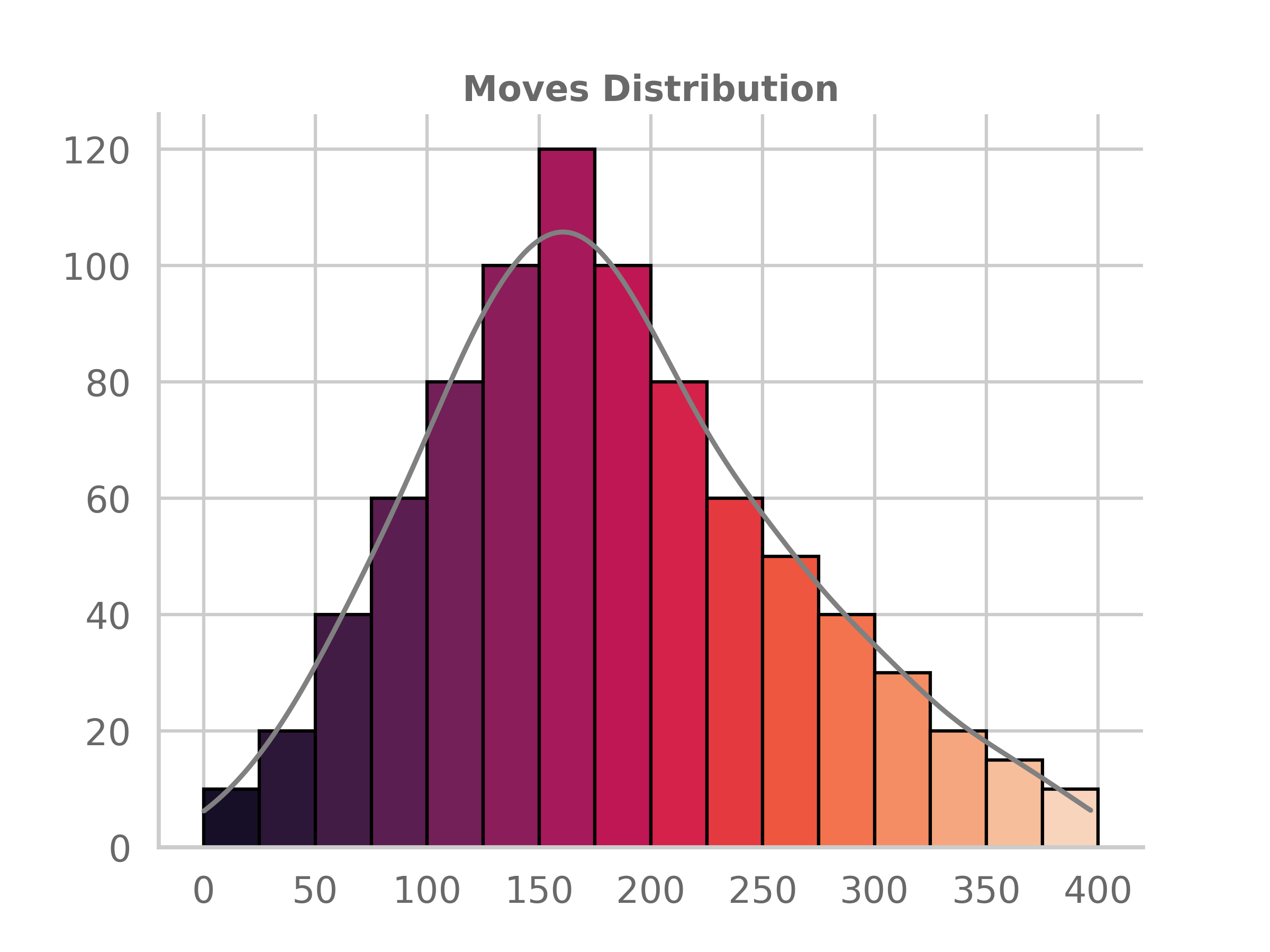

The distribution of the number of moves in these games was alarming. On average 200 moves of chess were played in these games - that is a substantial amount. For reference the longest game in the 2023 World Chess Championship was 90 moves [3].

Did We Find Our Shakespearian Monkey?

The results at large don’t reflect a fundamentally different picture of chess than what we expect at the top-level. If I were to just tell you that an overwhelming number of chess games end in draws with white holding a slight majority you wouldn’t be surprised.

Instead of undermining the sanctity of the sport I think this does the opposite. This exercise shows that chess is practically a perfect game, two players playing with the same “strategy” of randomness can be expected to draw the same result as two players playing with near-optimal strategy. If that isn’t beautiful I don’t know what is. And it was beautiful to me until I actually started digging deeper into the content of these games:

This was - chefs kiss - beautiful. Three moves is the fastest possible game of chess resulting in checkmate and its nice to know that our randomness got there.

On the other hand - I don’t even know where to begin with this. Naturally, this game ended with insufficient material, mercifully putting the two kings out of their agony. The game lasted 367 moves but there is no point breaking the game down in totality because it makes absolutely no sense. Instead here are a couple of points of interest:

- According to the chess.com Master’s Database [4] this game is totally unique after move 2 which has to be some type of record. Unfortunately, it also serves as a precursor of the events to come.

- Move #122 was the first mate-in-one opportunity in the game, in fact for around 80 moves (move 80-160) black was in clear control either having multiple mate sequences available.

- The game didn’t end how you would expect it to - with kings idly circling pawns waiting for the heat-death of the universe. In fact black had a chance to win until move 360 before throwing its’ rook away.

Take That Random Man

I think it’s time to put random to the test. How does our blindfolded random player perform against real users. Now instead of gradually building up confidence let’s go all out pairing our random chess player against the top-shelf Stockfish engine [5]. To be extra courteous I’m even going to make Stockfish play black for a sliver of disadvantage.

This simulation was run as so:

def play_random_game():

engine = chess.engine.SimpleEngine.popen_uci("/opt/homebrew/bin/stockfish")

board = chess.Board()

while (not board.is_game_over()):

if board.turn:

moves = list(board.legal_moves)

random.shuffle(moves)

board.push(moves[0])

else:

result = engine.play(board, chess.engine.Limit(time=0.1))

board.push(result.move)

engine.quit()

analyze_board(board)

for i in range(500):

play_random_game()

I didn’t really see an adequate way of creating suspense with these results. All 500 resulted in checkmate with black (Stockfish) winning 500 times.

.png)

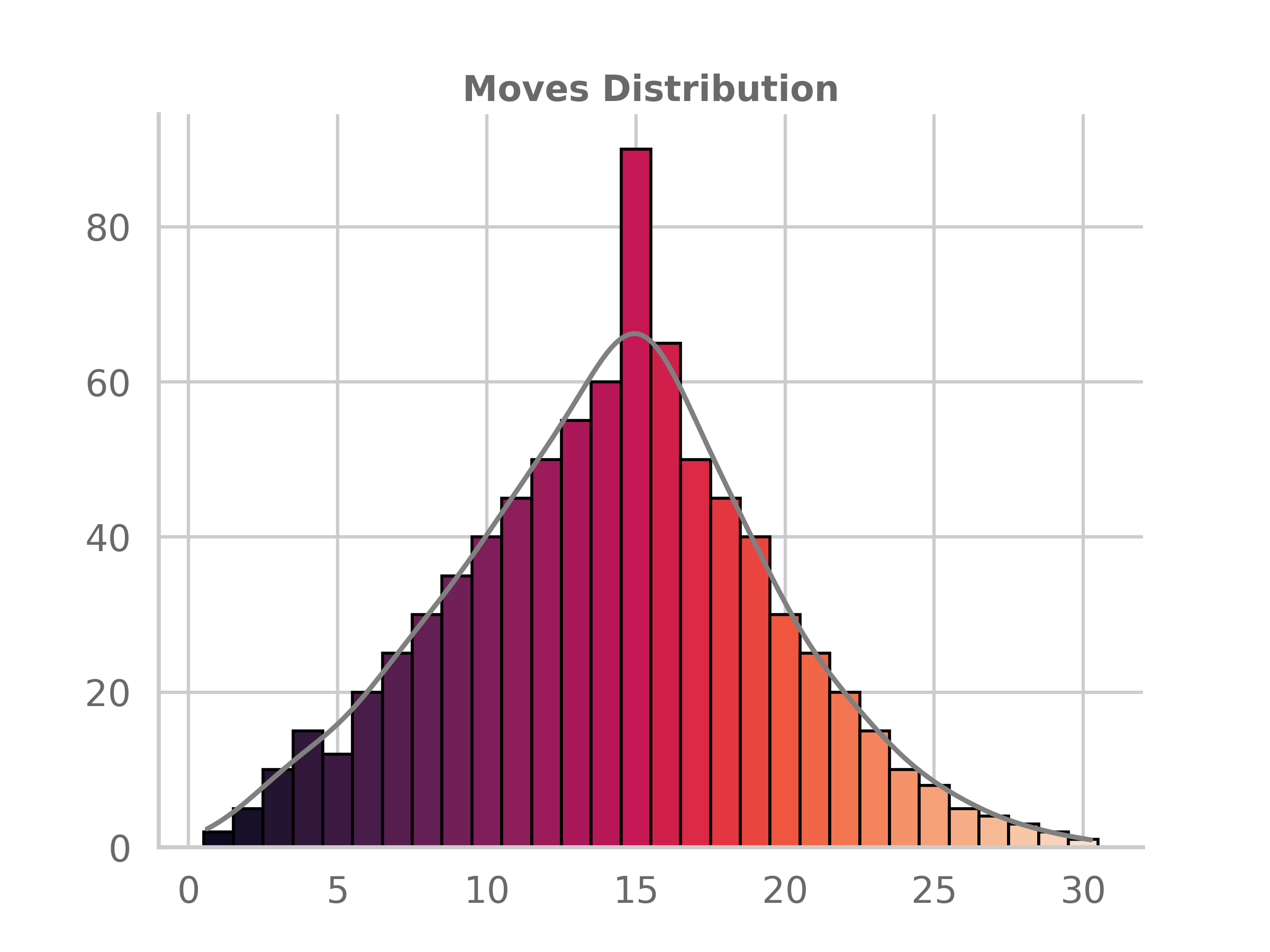

Games lasted on average 15 moves or about 13 times shorter than random v. random games. But interest in randomness over large samples comes at the extremes. The shortest movie recorded in these 500 games was 4 moves with a similar structure to the fool’s mate.

But the longest game recorded was 29 moves. Which is no small feat. Imagine, running 1000 games, 10,000, or a million. Eventually we will reach a point where the number of moves that our random player is able to last will grow larger and larger until … it wins. This is a product of two things, the power of typewriting monkeys and the mysteries of chess.

Typewriting monkeys overwhelmingly produce gibberish but if you spend time sifting through their prose they produce that one seminal work. That which is more beautiful and provocative than anything we could produce in our rational but finite world.

And the second factor that allows these results is that chess is hard. If this was a game of tic-tac-toe a random player playing a solver could only ever hope to get a draw. But even the best chess engines make no guarantee of perfection.

Much like the unpredictable keystrokes of a monkey at a typewriter or the seemingly foolish decisions of a chess player. It is this very chaos that gives birth to masterpieces and marvels beyond our comprehension.